A Marketing Hot Take, 20 Slimy Adventures, and the Lure of Abracadabra

Product Marketing as an ego killer, twenty adventure hooks for strange Slime encounters and a brief explanation of the Mage archetype in pop culture

Why Pay for Marketing?

A couple of interest-free thoughts from our marketing guy

Today, I’m not here to tell you how to make money with tabletop RPGs online. Mainly because, as of now, I can’t show you the receipts to prove I know how. I could do so in other industries, where I’m on home turf, but in the TTRPG space, I’m still little more than a guest.

What I can do is ask questions to figure out if we’re at least creating something that people genuinely want to play.

You Can Make Easy Money if You’re Evil (or Already Have ALL the Money)

First thing: if you have money, lots of it, or significant influence, you can often brute-force your marketing and rake it in with your games. It doesn’t need to be anything decent; just a recognizable brand, a good word from some community giant, or just an ol’ good thick roll of cash will suffice. If the product ends up being terrible, it doesn’t matter: you’ll break even on the first day of sales.

If you have a bit of money but not an overwhelming amount, you can be a jerk and employ all the classic pyramid-scheme-adjacent tactics, just one step removed from outright scams. Do pre-orders disguised as crowdfunding campaigns, promise the world, hide the actual costs of your product to look like you’re being successful, recycle as much content as possible, sell dropship trinkets as the main attraction for your anemic A5 booklet priced at $40, and then, make sure to congratulate yourself because hey, you really know how to do marketing! If you’re lucky, this might work a couple of times tops, but can you imagine the satisfaction of winning?

Here, we’re not talking to the first group, for whom we are merely footnotes in a forgettable book, nor to the second, who we hope will someday end up in the Book of Grudges of a particularly combative dwarf.

For ordinary folks with zero or near-zero budgets, what are the steps to break into a market full of sharks, piranhas, and those annoying little algae that stick to your thighs and are just plain irritating?

Your Product Should Be a Game, But Not All Games Are Products

Let’s start with something that seems obvious but often isn’t. Give me a good product, and I’ll find a way to sell it, but I wouldn’t have the faintest idea how to do that with just a game. “But games are products.” Yes, but not always. A game might not have an authentic audience; it could be incomplete, too quirky, or similar to something already on the market. And there’s nothing wrong with that! I have a couple of games myself that, to be honest, aren’t products. And that’s okay.

However, a genuine product must have an audience, a typical reader and player, and a quality standard that puts it on par with other alternatives in the same space. Moreover, it should have some element that sets it apart, making people say, “Ah, it’s like X but with Y and Z!”

If you know who your audience is, you know what they like. If you know who your typical reader and player are, you know where to find them. If your game has elements that genuinely differentiate it, you’ll know how to talk about and communicate it effectively. Look, it’s almost as if we have the beginnings of an essential product marketing strategy, and all we’ve done is figure out what kind of game we have on our hands.

Whether you’re doing your own marketing or planning to pay someone to do it, this is a step you absolutely cannot skip. You should do it before finishing your writing; sorry to say this to the more rebellious creatives out there, but your audience should influence your game’s design decisions.

Vanity Design and Where to Find It

“But I write things that I like.” Okay, that’s perfectly fine! It just means you’re not trying to create a product. And if it ends up being a product, it’s a lucky break that it aligned with the market. You know those success stories where people say, “Wow, I just followed my instincts, and my dreams came true”? That’s a perfect example of survivorship bias. Behind every person who followed their dreams and succeeded, thousands of fools pursued a dead-end path, refusing to ask themselves if they were talking to a non-existent audience. Curiously, even those who succeed in following their dreams often risk failure when they try to change their formula or branch out.

Again, are you writing for yourself and your friends? No problem; unconventional, spontaneous, and offbeat games can be awesome. But if you want your games to be played—which is not a minor detail and is a core part of our strategy—you must let go of vanity and think about what others want from your game.

You are not your audience. You are in service to your audience. You can choose one that looks like a lot like you, but they’re not you.

Why Do You Need Marketing?

Because you need someone (or need to become someone) who can take the raw stuff of imagination, the platonic ideal of a game, and bring it into the real world, where it can be compared with everything else. People in marketing are often disliked for “polluting” your ideas, primarily because of this annoying habit we have of trying to keep you from starving—and I get it. Sometimes, we’re pretty obnoxious. However, marketing can also be a healthy way to build a genuine relationship with readers, always keeping a pulse on their wants and needs. Being successful is challenging but possible if you’re in tune with your community, but it’s prohibitive if you haven’t learned to listen first and let that ego of yours go.

Choice and consequences

Let’s be clear: I desperately want to read your next games, and I hope they carry your genuine voice.

I don’t think you need to become commercial, nor do I want to imply that there’s some magical formula to transform living, breathing writing into some soulless digital Soylent Green that will make you incredibly rich.

I simply believe it’s important to know who you’re writing for and your goal as an author and, in many cases, as a self-publisher. Gaining clarity on these aspects and accepting the consequences of your creative choices is both crucial and liberating.

Take us, for example: Epigoni is one of my favorite games. To this day, I bring it whenever I need to run a game for strangers wherever I go. It’s thematically rich, poignant, cultured, queer, and outrageously fun. And yet, as a product, it doesn’t work as well as it could. It’s the perfect game for creative and experimental tables, for players who love fiction-driven games with distributed narrative authority. It can be lyrical and profound but as absurd and chaotic as the wildest episode of DanDanDan. Yet we couldn’t communicate all this effectively, in form or substance. The game comes across as complex, cerebral, and too open-ended, with flexibility that paradoxically paralyzes new players. The illustrations are beautiful but static, giving the impression of something cold, elitist, and detached. But it should be an action game about rebellion, a middle finger to Fate—it’s bloody Mythpop!

We probably should have sacrificed some of that creative freedom for a more explicit structure that could better convey the game’s style and atmosphere. We should have made the visual design messier, maybe less polished, but more vibrant, dynamic, and colorful. Would it still have been Epigoni? Perhaps it would have been less the Epigoni I love now, but maybe it would have been the Epigoni a wider audience could have loved. We can’t change the Epigoni Core Book and Epigoni Essential (at least for now), but all our decisions for its second sourcebook, Godnet Database, directly respond to all the weak spots we analyzed before. We’re still working on it, but you can see the difference simply from the illustration below.

That’s why you need marketing: not to sell more of your games, but to understand what you are willing to do to help them find the people who genuinely appreciate them.

Toybox: Slime Adventure Prompts

We published a system-agnostic sourcebook focused on slimes a few months ago called Vol Flint’s Guide to Slimes. We thought to ourselves: what’s a monster without an adventure hook tied to it?

For this reason, we created a rollable table of twenty prompts—one for each slime in the manual—to immerse your table in some delightful gelatinous chaos!

The Path of the Mage

“Ask, and it will be given to you; seek, and you will find; knock, and it will be opened to you.”

Human intellect has condemned us to unhappiness since the moment the first hominid lifted their gaze to the heavens and began asking questions, as if already aware of Socrates’ famous phrase about true wisdom lying in the knowledge of one’s ignorance. Yet the Universe is a mysterious system governed by laws still unknown to us, and our need to make sense of it all has been a driving force behind human storytelling. This mystery often manifests in the “sense of wonder” of a child discovering the world, the cosmic horror of someone uncovering the Truth and being unable to bear it, or a maddening thirst for knowledge that condemns us, like Dante’s Ulysses, to reckless flights of fancy—often wildly speculative ones.

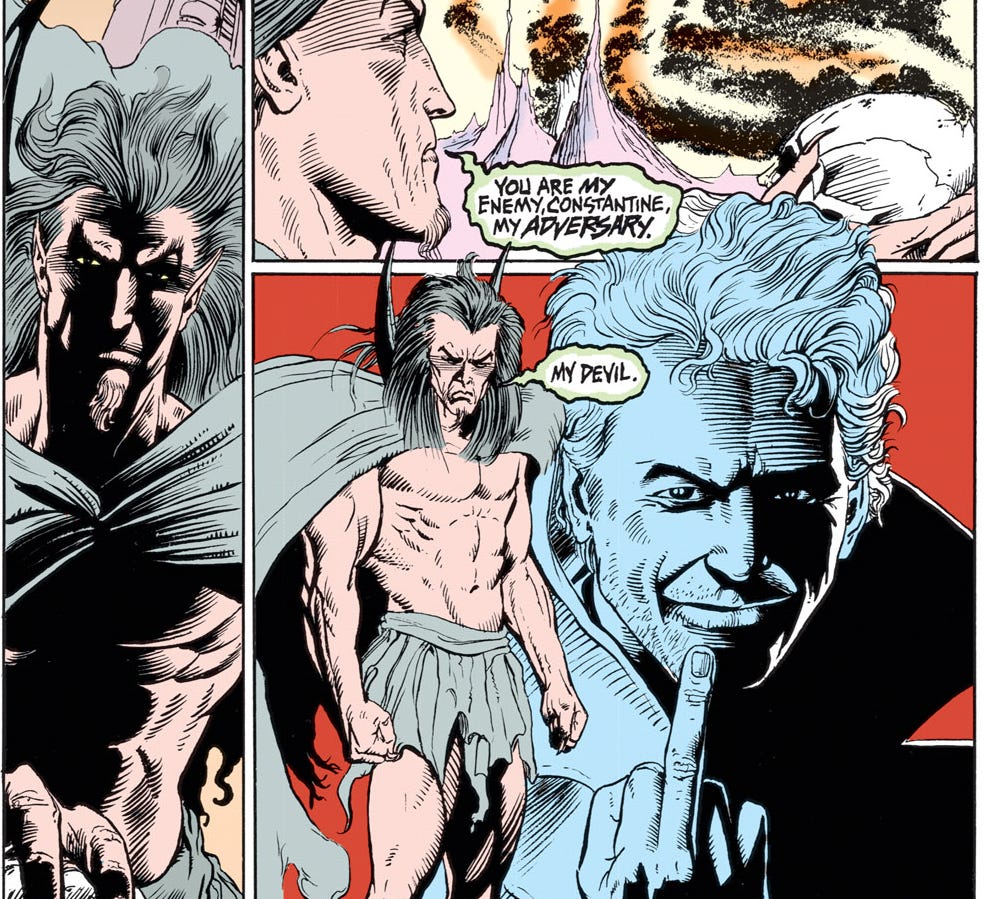

If this need finds its expression in the archetype of the Seeker, its resolution is embodied in that of the Mage, the figure in contact with the mystery. The Mage is the advisor who knows how to direct efforts toward harmony with creation, has grasped the game’s rules, and chooses to play with awareness. Naturally, ancient and modern narratives abound with such figures. Yet, thanks to the growing influence of pop culture, fresh approaches to the mystery of magic have emerged—ironically, ones that echo more ancient traditions than the stereotypes dominating fiction for decades.

Take, for example, John Constantine, an expert in the occult arts who often relies on wit rather than spells to escape dire situations. A cynical bastard consumed by guilt, he’s a mage hailing from Newcastle’s working-class neighborhoods. This, however, barely scratches the surface of Alan Moore’s creation, which, under James Delano’s guidance, evolved into the character we all love to hate while begrudgingly admiring him. Much has been written about Constantine, notably his long-running Hellblazer series under the Vertigo label—a gritty sandbox of humanity’s darkest despair, most twisted desires, and deepest passions. But amidst all the bleakness, it also showcases humanity’s ability to rise above, to flip the gods the proverbial middle finger, and to reveal the qualities that have enabled our survival, time and again.

In his simplicity and rare use of actual arcane arts, John Constantine paradoxically embodies what magic truly is: the abracadabra of Crowleyan fame. This word lets the Mage’s will shape reality. Yet Constantine isn’t just a magician or a conman; he’s also a deceiver, especially to himself. He wears his solitude as a badge of honor to mask his fear of endangering those close to him, hides a tormented soul behind biting humor, and refuses to show weakness to others—even though he fears death and the consequences of his reckless actions more than anyone else.

On the other hand, we find entirely different aspects of the Mage archetype in manga and anime, such as Fairy Tail, a now-concluded series where, in the world of Earthland, individuals gifted with magic (around 10% of the population) form guilds to undertake missions for rewards. Beyond its quasi-video-game structure, which has since become a hallmark of many modern productions, Fairy Tail stands out for its deeply emotional approach to magic. “In Fairy Tail, everyone has a scar on their heart” becomes a symbolic phrase for the protagonists and everyone, as the rules of magic—often ambiguous and serving the narrative—stem from the power of emotions.

The strength of bonds, love, anger, fear, frustration, and the entire spectrum of human emotions become the symbolic “magic words” that tap into magic because “magic comes from deep within the heart.” Thus, the growth of a true mage inevitably involves pain and acceptance, transforming anger into justice, cherishing connections, and navigating the stages of the Hero’s Journey that lead to self-actualization. In contrast, dark magic draws its strength from loneliness, unresolved negative emotions, ambition, and obsession—fueling the creation of Demons, entities that, in their way, reflect these aspects of humanity.

So, while the West—heirs of Crowley—present magic as a verbal trick, a sleight of hand with tarot cards in which understanding the world’s rules leads to rational exploits, the East offers a vision in which the laws of creation are shattered by feelings, passions, and bonds, portraying humanity as an integral part of the whole.

But in the end, what truly is the Mage? Who can say? After all, a great illusionist never reveals their secrets.

Yeah, before we forget, we will release the next free product in a couple of weeks, and subscribers will be the only ones able to access it for the first week.

If you want to be the first to know what it is, follow us on Instagram. It’s a cool account, trust us.

With ref to the first part, you made me think a lot about why we are here and what we are looking for... i have to make my mind up, too many thoughts at the moment! Thanks for your hints!