Mythical Pubs, Localization Choices, and Aliens

Why do we produce our games in English? And why Alien was such a disruptive movie? You don't care? Well, we still have free stuff for you to play with.

Just a quick intro

Welcome to Tales from the Odd Ones, our monthly Substack entry full of wonder, creativity, free gaming content, and a tiny bit of spite to spice things up.

Every month, we will talk about a lot of things:

musings about the RPG industry;

game design concepts that intrigue us;

rants about gaming stuff that we find funny, insufferable, or both;

free modules, characters, monsters, and adventure hooks for you to enjoy;

pop culture critiques, from comic books to certified kino™ masterpieces;

announcements and product launch timelines.

Only some of these columns will be present each month; we know you have a life. The only thing always present is free stuff for you to download. You're lucky, uh?

Localization woes

As Italian authors, we already know that this question will become recurring, considering that Italy is one of the most famous countries in the world for its attention to movies, video games, and TV show localizations. Now, as much as we love our native language, it is almost impossible to produce and distribute a dual-language project as an indie label of our size. Let us explain why in three points.

1. We write in English to reach a wider audience

We want you to play our games, which is not easily done in an environment as small and saturated as the Italian market. To give some numbers, Italy’s most significant RPG-related online communities go from 15 to 20 thousand subscribers, and flagship media projects like Inntale exceed 60k followers on Instagram. Yet, even today, we still pop the champagne and cry international success when a project reaches 2,000 backers on crowdfunding platforms; indeed, it is an impressive number, but if we take into consideration that our Italian-only Blood Engine Lite (the framework behind our July project, by the way) has been downloaded 1,200 times, it gives a little bit of pause.

How many of these games are actually played, anyway?

The fault lies not with the public or the publishers (at least this time!) but with the Italian market, where there is a significant atomization of the audiences: every single one manages to be ridiculously bite-sized and pretty distinct simultaneously. The projects on Kickstarter often showcase games that play second fiddle to the overwhelming array of superfluous add-ons. The incessant influx of new products, coupled with relentless FOMO-driven communication strategies, creates a marketplace reminiscent of the Yiddish joke about the salmon—items seem to be created solely "to be sold and bought" rather than to be enjoyed. You can prove this in flea markets, where recent products are offered for deep sale and are often in mint condition, being browsed once in some cases.

2. Even digital products are pretty expensive

I know it isn't polite, but let's discuss the cost of publishing briefly: it costs a lot. In addition to money, you should also consider time and mental energy. Still, limiting ourselves only to the ol' cash, it doesn't take a Nobel Prize winner in mathematics to realize that producing one game costs less than producing two.

Yes, the printing itself of a project is the least expensive part of it: a product printed by an Italian print shop in paperback format costs around 3-5 euros for about 240 pages. Still, you need to splurge for layout, art, editing, writing, and promotion. As you will understand, a free or PWYW product is always at a loss if done professionally, and consequently, as much as you can offset the art cost using it for more than a single book, works like layout should be calculated according to the volume of pages which, as you will imagine, doubles if you do in two languages.

We will always try to publish our works in Italian and English when possible, but this becomes unsustainable for our most significant projects, and we would risk jeopardizing the Oddplan project.

3. English is the lingua franca of the hobby

Let’s be real: you know English. If you have come this far and understood the text well enough to know what I'm talking about, it is clear that you have a good grasp of the language. And why shouldn't you? If you are under 30, it is part of your daily life. If you are over 30, you had to learn English when you were young because localized video games were a rarity, and translated role-playing games were sparse.

It may not be the most comfortable solution in the world, making reading a little more tiring. However, at least the advantage of having an Italian team is that you still have the opportunity to ask questions about CopperHead games and Blood Engine games in our Italian communities. We are here to listen to you and answer any questions.

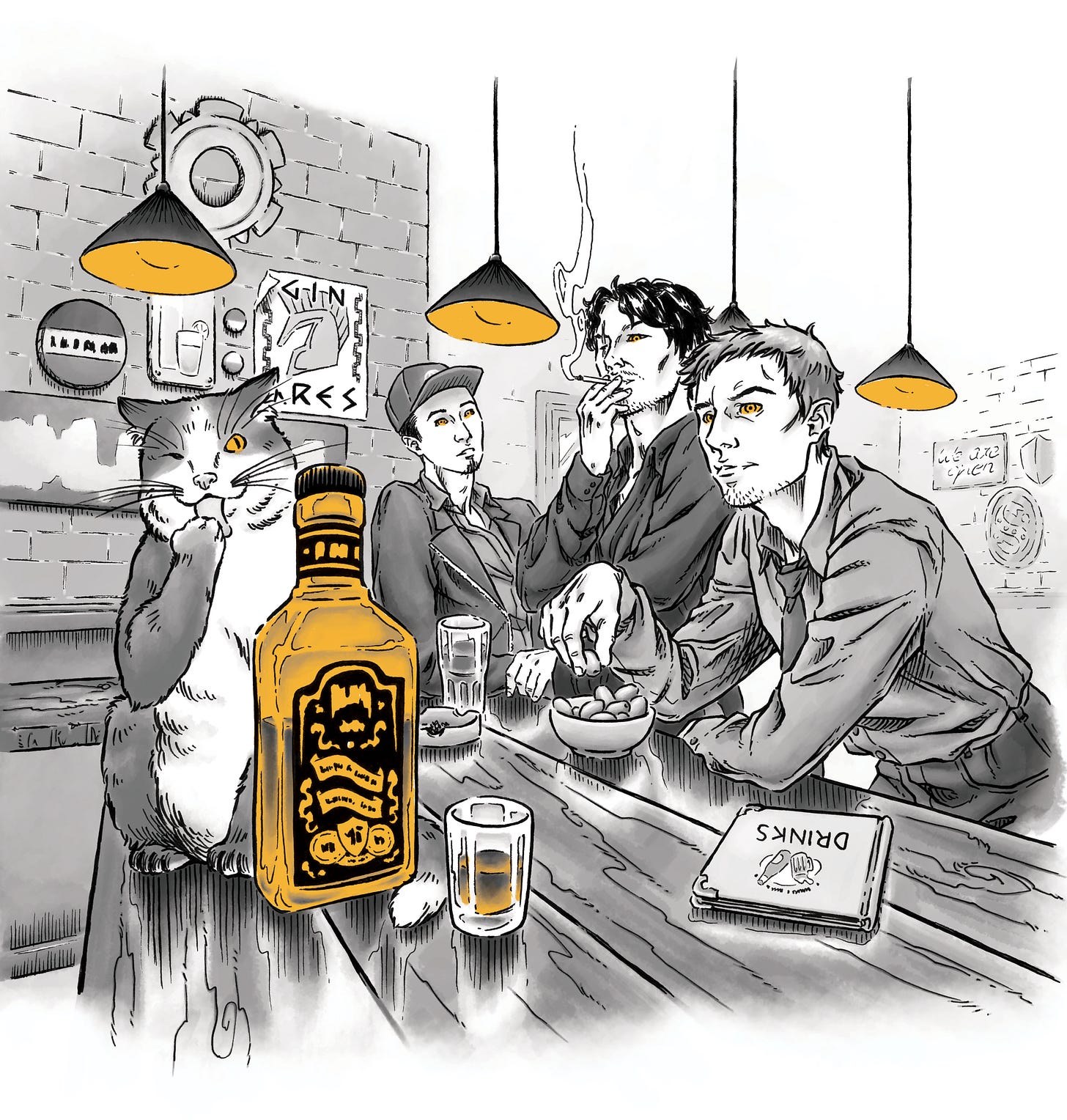

Toy Box: Pub Crawl

A Gods of London Saga can only function with at least one little detour to a Pub, better if suited for Gods and Legends.

Today, we present you a Pub Crawl rollable table for Epigoni. You can use it to find the right adventure hook for your next tipsy escapade or become the backbone for a sprawling The World's End-like campaign. To choose randomly, simply roll a d20 and have fun!

(Despite what we said before, Pub Crawl is both in English and Italian. We already had the Italian text, and the layout was easy to modify. Have fun!)

You can find The Gods of London Vision on Epigoni: Essential, free to download on itch.io and DrivethruRPG.

Take off and nuke the site from orbit

More than 40 years ago, Alien chittered into theaters, leaving a mark that would infect society more than a face-hugger can do with a host body. The alien that penetrated the fabric of the collective imagination tore what we had previously pictured of the menace from space. The myth of the xenomorph was born out of a rare mixture of overtly sexual aesthetics, the deformation of motherhood (think of how the alien reproduces using a form of sexual violence that turns anybody into a womb, ready to eject the larva of what will be the ultimate predator), and the feeling of a historical crisis in western values.

The evolution of human thought is tonally closer to Lovecraftian cosmic horror than to the optimism of Asimov and earlier science fiction: astronauts are not fearless explorers but mere miners in search of materials to extract, and spaceships are not splendid chrome-plated vessels equipped with incredible technologies but brutalist barracks moving in a cold universe that ignores the race that would like to be its master.

The alien itself is not a creature that cares specifically for humanity's destiny; if we think about it, its function is only to be a perfectly designed death machine whose ultimate goal is extermination. It could easily use any creature as a host; in the third film, it is indeed a dog that serves as an incubator.

We can easily consider Alien the precursor of the deconstructionism that will haunt the 1980s by giving us such masterpieces as Alan Moore's Watchmen or DC Comics' Crisis on Infinite Earths. The beginning of the Bronze Age throws in our faces how the line between human, nonhuman, and inhuman will be blurred soon and how, in the face of the questions posed by cyberpunk, even Space Opera has to bow its head. The collective consciousness interpreted by the new wave of authors established the failure of the utopias of the 1960s and 1970s, with the USCSS Nostromo's voyage leading us to the ominous conclusions of a journey influenced by the freedom-first narratives of the prior decades and the contemporary disenchanted reflections on unregulated capitalism.

In a claustrophobic environment where you are nothing but a tool, precisely like the android accompanying you, in the hands of a megacorporation that sees space as just yet another revenue stream, your life is worth nothing. It is worth so little that the actual conflict consists of who will be the first to eliminate you: the faceless alien or the executive who, from afar, decrees your death to safeguard a potential tool from which to make a profit? Can you call hostile the first nonhuman species you encounter if it's none other than an alpha superpredator with no purpose but to kill everything on its path? Is not the xenomorph much more like a machine capable of self-reproduction by exploiting external resources than an actual animal? The Alien is a hyper-performing being that colonizes and extracts from its host body what it needs without regard to the consequences. The apex predator teaches humans that they can be at the top of the food chain on their planet but are hopeless against something so pragmatic and efficient, while in a distorted and diseased way, even in its own physical and mental structure.

The Alien is a monster that devours everything without questioning itself, and it is not hard to compare to its prey trapped in a box adrift in a universe that is not hostile; it is simply deaf and devoid of mercy. Alien and the Xenomorph thus open the antechamber to this tremendous reflection: perhaps the Great Crisis of the Twentieth Century was never really metabolized but was swept under the rug and slowly expanded into all that is fiction. A terrible thought that would erode any positive idea, infect it, and show the public that the optimism of the previous century is now the main course of a banquet at which we have binged in the name of ever-increasing efficiency. At some point, we realized something: evolution is not a gala dinner.

Yeah, before we forget, we will release the next free game on July 20th, and subscribers will be the only ones able to access it for the first week.

What game, you ask? The Alien article was not as random as you may have thought.

Did you enjoy this post? Why don’t you share it with a friend and make him (or us) happy?

I strongly agree with your choice of language, thank you kindly for the Pub Crawl, and love you deeply for this article on Alien. Cheers! ❤

I sense a foreshadowing for a sci-fi Blood Engine game set in a prison planet?