Can’t stop an evolving Goblin

Discover how we steered a wreck of a TTRPG project and found its authentic voice in the second Making of “Goblin.”

As in the best stories, it’s important to start with a big question: “Where were we?”

As we mentioned, Goblin has had a somewhat troubled publishing history until we decided to take matters into our own hands, embrace self-publishing, and bring it under the Oddplan umbrella. At that point, it became necessary to revisit the manuscript, which had turned into a grotesque patchwork of suggestions from different publishers trying to make it “more suitable for their catalog,” and start over. From scratch.

Because while Goblin—which, let’s remember, is still a temporary title—remained in its digital limbo, its original author had completed the first two books of Epigoni, Corebook and Visions, which uses the same proprietary system, the CopperHead System (CH), and had written a new engine, this time in OSR style: the Blood Engine. Meanwhile, the rest of the Oddplan team had also begun experimenting with various projects using CH, pushing the system in new directions. After all, the beauty of game design is experimentation, right?

During this time, the game was taken to multiple public playtests and was naturally influenced by player feedback, as is to be expected.

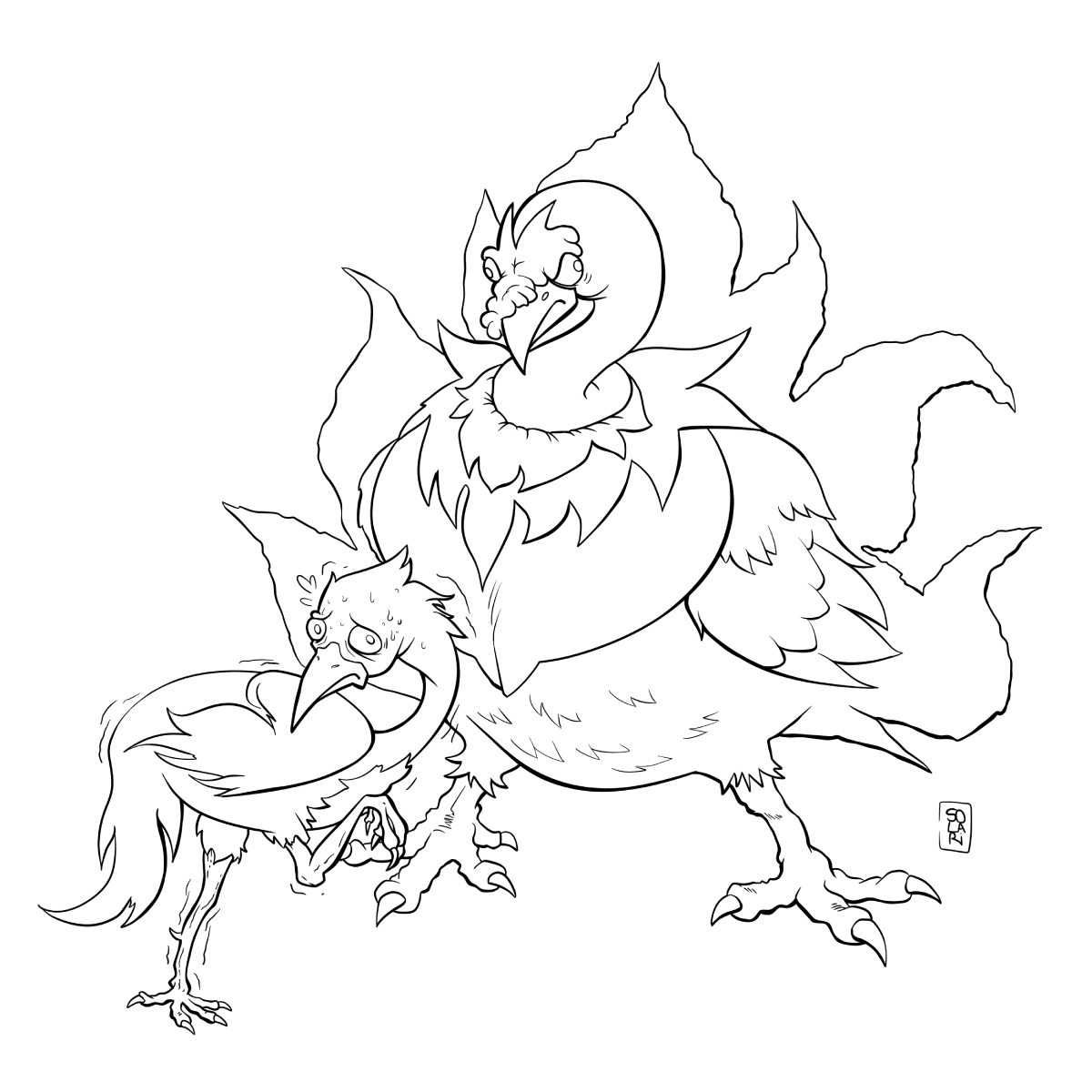

So, in a way, we’ve returned to our roots—to that style we’ve always loved, inspired by the simple goblins of Games Workshop, while adding a lighter, more cartoonish touch to the fiction, hence the motto: “It’s just a goblin, after all.”

What is Goblin now?

Goblin has gradually evolved into a game where the core themes are exploration, discovery, and problem-solving through the players’ ingenuity and cunning as they interact with the game world—alongside the obvious challenge of surviving in the dungeon’s hostile ecosystem, which is quite unforgiving for such lowly creatures as goblins.

The tone is anything but epic: player characters are fragile, cowardly, and expendable, yet this doesn’t mean they can’t embark on thrilling adventures and achieve legendary feats. Legendary for goblins, at least.

Even though they have no regard for life and safety—neither their own nor that of others—and live out absurd adventures with a dark twist stemming from the real consequences of their actions, this doesn’t mean the protagonists are rotten to the core, grim, or outright evil. Think of it like Tom & Jerry: the violence is extreme and exaggerated, but it should never feel offensive or disturbing to the table. A funny scene should always take precedence over one of deliberate, pointless cruelty.

What’s the gameplay style?

In terms of themes, Goblin leans much more towards OSR rather than Middle-School RPGs, partly due to the use of procedural tables for generating areas to explore and, when needed, for randomly generating not just encounters but the monsters themselves.

This stylistic choice places Goblin within the modern New OSR movement, as it blends elements from both worlds: the exploratory, surprise-filled nature of OSR games, and the collaborative world-building approach of New Wave RPGs, where storytelling is shared across the entire table.

Goblin is designed for audiences under 35 because of its pop culture references (for instance, the evolution of characters and monsters is a clear nod to Pokémon and the System concept from Isekai anime) and its streamlined game mechanics.

The rules are light and encourage interpretation and scene creation through the use of Keywords. It’s a game that doesn’t require a heavy time investment in character creation but offers a high degree of customization—especially in play since it’s up to the players to describe how they use what they have.

While Goblin works well as a one-shot due to its simplicity, it also fits long-term campaigns thanks to its level-based progression system and the ability to explore a chaotic and unpredictable world.

Same system, different feel

The CopperHead System has been adapted quite differently in Goblin compared to Epigoni, making it more akin to the fantasy RPGs we love—those rooted, like it or not, in classic Dungeons & Dragons.

Player characters have classes and level up. They have three core Attributes and two additional Keywords that can be used during rolls to increase their chances of success. One of these Keywords is the usual Skills, but the second is more unconventional: Mutations. These are randomly determined traits that physically alter the goblin’s body. However, a Mutation can also be used by the player to boost their Rank during a challenge—or by the GM to increase the challenge’s difficulty in certain situations.

Regarding character mechanics, we removed the Status-based system from Epigoni, which required too much bookkeeping and replaced it with a four-section Wound Counter. Each hit fills a section, and once the counter is full, the character is removed from the scene.

Statuses still exist, but they are now separate effects triggered either by specific monster abilities or when the first and third wound sections fill up.

We wanted a lethal but not deadly game—something also evident in the Blood Engine. When a goblin leaves the scene, they roll on a table to gain a Misfortune, a lasting complication that will make their life harder in future sessions.

Finally, upon reaching a certain level, characters can specialize into a new class called an Evolution. Evolutions enhance the unique traits of each class, unlocking new gameplay options.

Combat & Mechanics

We’ve moved away from the pure narrative approach of Epigoni and early CH. Unlike Epigoni, characters in Goblin act in turn-based combat, with initiative determined by their Load (yes, we even added encumbrance). Each character gets one action on their turn and one additional reaction outside of it.

Since Goblin’s enemies aren’t complex, metaphysical beings with bizarre, reality-warping powers straight out of an Araki manga (seriously, check out our Essential, and you’ll see what I mean), we’ve added a simple but effective mechanic to make combat more interesting.

In addition to their Rank and Wound Counter, every enemy in Goblin has a stat called Armor. The GM can spend Armor points to downgrade an attack roll against an enemy and take control of the consequences.

You can’t kill them all

As you can see, even though the Italian publishing industry has knocked around this project and we have been through an emotional rollercoaster more than once, none of that time was wasted.

And isn’t it ironic that, in its way, this game has gone through an evolution of its own?

Goblin will be released at the end of April, and we’ll start revealing more about the fully digital manual, which will be available in stores in just over a month. For our subscribers, in addition to the usual free monthly games, we’ve decided to offer a 50% discount on the cover price as a token of our appreciation for your support during these months of experimentation. After all, you didn’t insult us for the pizza delivery game!